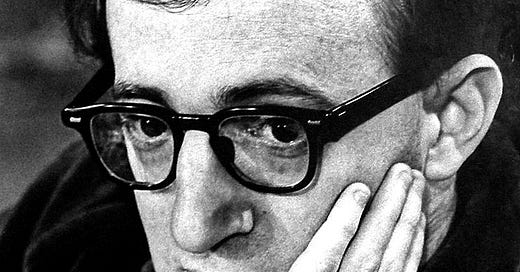

One of the most original and important filmmakers of the last 75 years, Woody Allen has made several of the greatest films of all time, such as Annie Hall, Manhattan, Crimes and Misdemeanors, Hannah and Her Sisters, and many others. His influence on comedy, screenwriting, and directing cannot be overstated, and when I found out that I was getting the chance to interview him, I was ecstatic. Here was a man whose movies I had grown up on, who had shaped my worldview and changed the way I viewed humor and life. Much of it had to do with the age I watched his films. Annie Hall was the first “mature comedy” I ever watched, having just graduated from cartoons like Tom and Jerry and Alvin and the Chipmunks. What is so distinctive about Woody Allen’s filmmaking, and what still strikes me today is that he writes people who are real, but also funny. If this sounds banal, let me explain.

When you watch a comedy like Mel Brooks’s The Producers or The Marx Brothers in Duck Soup, you're very much aware that these aren’t people you’d encounter in the world, no matter how hilarious they are. Nobody has that searing, super-fast wit like Groucho Marx, nor that ironic, conniving cynicism like Zero Mostel does. Woody Allen draws his comedy from the real world, and his characters dance on the precipice between comedic fiction and very real people. I’m sure many people have encountered someone like Alvy Singer in their lives, the nebbish, neurotic but endearingly funny friend you have, or someone like Annie Hall, an idealist, very affectionate, but somewhat strange cousin that shows up to family gatherings once in a while. Woody Allen’s comedy draws from the people we all know and exaggerates their personalities to the point where it is very funny, but not so much so to the point where they become alien and unreal. He may very well be the only comedic writer to ever do such a thing.

Mr. Allen very kindly agreed to sit down with me for an interview over the phone in which we covered a wide variety of subjects over his more than 50-year filmmaking career, including his music, Ingmar Bergman, and the many people he has worked with. I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to Mr. Allen for this opportunity and to his assistant Pamela for arranging this.

TI: Thank you very much for sitting down with me. It’s a real Purple Rose of Cairo moment. It’s like you’re stepping down from the silver screen.

WA: Of course. And if you need any help, I’ll be glad to answer your questions. Just ask me anything you want.

TI: If you’re okay with it, I’d like to start by talking about the music in your films.

WA: Well, the music comes from the music I grew up with and loved so much. You know, I grew up in an era where it was radio, so when you got up in the morning you turned it on because it was effortless. You didn’t have to concentrate on a television screen, and you just turned on the radio and went about your business. You got up, got dressed, had your breakfast, and the music was always playing. The music in that era was very good, it was the music of the great American songwriters like Gershwin, Kern, Cole Porter, and Berlin, and the people doing the music were people like Benny Goodman, Billie Holiday, and Frank Sinatra. It was extremely good popular music. So I liked that music, and when I was doing my first two movies, I gave the job of scoring them to Marvin Hamlisch, who’s a very good composer, but I found that giving my films to someone to add music to was a pain in the neck and it took a long time, and they didn’t get exactly what I wanted. So, I started to just go to my record collection and put my records in. When we cut the picture, we would just kind of imagine what would be the right music, and we’d take a record off and play it next to the scene, look at it, and sometimes it was right and made the scene look ten times better. Sometimes they guessed wrong, and the record would come off and we’d find another one. And that’s how we did it—that was the most fun of making the film, when we finally had it together, selecting something from the vast library in the cutting room of great music like jazz, popular music, and classical music. I could score the picture myself, so to speak, instead of having a composer come in and score it. As I said before, the most pleasurable part of making the film was adding the music because the scenes came to life. It was fun, and it was relaxing to do. I didn’t have to be out on some cold mountaintop filming—I could just sit back and have my pick of the world’s greatest music. That’s what we did over the years, and it worked very well for us. We used a ton of songs, jazz, a certain amount of classical, and some opera. I rarely used, in fact, I never used contemporary music because I was never a big fan of contemporary popular music. My tastes stopped at about 1950. But that’s how we scored the picture, and everybody always looked forward to it.

TI: This is interesting, because I’m thinking about how you use Gershwin in your movies, and I remember reading in an interview you gave about how you had the idea for Manhattan after listening to Gershwin's music, and that got me thinking: was there ever another movie where you heard a song or piece of music and said “I want to make a film out of that, I think it needs to be made.”

WA: It wasn’t quite like that. When we started to make Manhattan I just accidentally ran and bought an album of Gershwin overtures and I started playing them, and there were some of those overtures I felt suggested scenes to me, and I would write those scenes into the picture. It wasn’t the idea for the picture itself, but the music would give me ideas for certain scenes in the picture, and that happened over the years in other films. Most recently, I believe, for Midnight in Paris, when I heard a Sidney Bechet record that we used at the beginning long before we conceived the picture, I thought to myself when I heard it “This would be a great piece of music to do a montage of Paris to.” I finally got the opportunity, and I knew when I was filming that montage of Paris that had been inspired by the record, that I was going to create great shots that were going to be very harmonious with that piece of music. That happened on a few occasions over the years where the music didn’t necessarily give me the whole idea for the picture, but it does give me inspiration for certain scenes, which I will then shoot knowing that I’m going to have that music playing in the background.

TI: Speaking more broadly, is that how it works with all your movies? Is the music always a vital precursor to all your scenes, ideas, and the mood you want to evoke?

WA: Yes. When I made my first movie Take the Money and Run, I was very much under the influence of Charlie Chaplin. I scored some of the scenes in that picture very, very poignantly, with very sad music, and it just never worked! The scenes just kind of dropped dead when you saw them, and they were an ordeal to get through. Then the editor, Ralph Rosenblum, came in on the picture and said “You’re killing your scenes with this music. You should take it out and look at the difference when I put in this piece of music” and then he would put in an up-tempo jazz piece, and then suddenly the exact same scene just came to life, and it was funny and exciting. So I realized the enormous influence of music on the scenes and the juxtaposition between the two. It was interesting because I was also at that time very much under the influence of Ingmar Bergman, and Bergman was against scoring. He thought music in films was barbaric. When I made Annie Hall and Interiors, those were very much under the influence of Bergman, and I didn’t score them at all. In Interiors it was fine, but in Annie Hall, it was rare at the time to see a comedy that had no scoring. I used source music, like if a character turned on the radio or went to a party, there would be music playing because that would be natural coming from the source on the screen. But I never scored anything when someone wasn’t playing music in the scene. I sort of regret that, I feel that if I were doing it over today I would put a lot more music into it, but at that time I was such a Bergman acolyte that I didn’t score those pictures. But I always did feel that with comedy, you just needed music. Because when a character was on a screen walking somewhere or driving somewhere, if you didn’t have music bouncing along with it, it just took forever for the viewer to watch—it was ponderous, and so music has been an enormous thing in my movies and it still is the case. When I made my last film, which was in French, I was completely aware that when I was younger and watched all the French movies that I loved by Godard, Resnais, Truffaut, and many others, they were all very much under the influence of American Jazz of that era, which is not my favorite, but still a very good era of jazz music. So, I scored my French picture, and I knew I was going to do it with Jazz of the 1950s, which you would’ve seen in a French film. A Louis Malle film, for example. It worked fine, and it gave the picture the French flavor that I wanted it to have.

TI: I want to shift gears for a second because I heard you mention Bergman, and I agree with your statement that Bergman was the greatest filmmaker in the world. I re-watched Wild Strawberries and I wanted to get your perspective on it because it’s about a man looking back on his life and achievements. You’ve seen this film before but has your perspective on this movie (and Bergman in general) changed at this stage in your career?

WA: Well, it hasn’t changed for me, because it was so impactful when I was a young man. I was in my early twenties or my late teens, and everybody was making films, but Bergman was making films and defying standard filmmaking, you know, he’d leave the camera lingering on someone’s face endlessly, for example. He was also dealing with existential subject matter that was particularly meaningful to me, and he was so superior to everyone around him both in his ambition and his execution. His films looked so beautiful in that black and white, and then later when he switched to color and did Cries and Whispers for example, and used all that red. That picture was so powerful. It’s very hard to disabuse someone of either their music or their influences, and it’s the same if I watch it now. It’s the same if I’m watching television and they’re showing an old Fellini film, or they showed Breathless the other day, and I realized how terrific it is that you never see anything like it today in terms of filmmakers and their audacity, creativity, and their ability to make it come off. The thing about Bergman, too, is that people nowadays sort of pejoratively think of him as an “intellectual” and “complicated,” but the truth of the matter is that he was a great entertainer. Take that arresting dream sequence at the beginning of Wild Strawberries. When people first saw that, they were hanging on their seats. You could hear a pin drop. They couldn’t believe how compelling it was. The rest of the movie is great and there is some great surreal imagery in it, and it was an extremely interesting movie. I think he did some films that were better than that, but it was a very arresting beginning to the films that came over here to America. For example, The Seventh Seal is a startling film, and even with a small film like The Magician, they were very entertaining. People were not making films like that, and he had such a great command of film technique. He was very entertaining, and people don’t realize that one of the reasons that he emerged in arthouse circles as a popular entertainer was because his films were not boring! People were entertained by films like Wild Strawberries, The Magician, and The Seventh Seal, and as he progressed to his later works like Persona and Cries and Whispers, people were still entertained. They didn’t see them and think that they were homework, or think that they were “intellectual.” His films were reasonably popular considering how obscure the subject matter was, and how erudite some of his points were. A picture like The Seventh Seal is a very entertaining picture. It’s not just a whole of Kierkegaardian and Nietzschean philosophy, it’s presented to you in an extremely entertaining way, and always visually beautiful.

TI: Bergman had the crimson that he used, and he worked with Sven Nykvist, whom I know you worked with. What did you learn from working with Nykvist? He was a genius in terms of the command of shadow and light, and I noticed that in Crimes and Misdemeanors, which is one of my favorite of your films, I’m very curious as to what you took from him and incorporated into your filmmaking.

WA: Well, first I would say that I didn’t learn as much from Sven as I did from Gordon Willis, because of the difference as to when I was starting when I knew absolutely nothing and was flying by the seat of my pants and trying to be funny, and saving myself because the jokes came out good and saved the picture. But back then I never knew anything about cinematography. Then when I started working with Gordon Willis, I learned everything about cinematography because he was a disciplinarian and a genius photographer. Since then, I’ve worked with great, great, photographers, and by the time I got to Sven, I’d worked with Carlo di Palma, who is also great. With Sven, there wasn’t a lot left for me to learn, Sven was just such a great natural photographer, like Carlo di Palma. With someone like Gordon Willis, he knew everything. He could call Eastman Kodak upstate and tell them how to make their film or whether they were using the wrong chemicals. He was astounding that way, whereas Sven was just like Carlo di Palma, a self-taught, natural, gifted guy. Sven used no lights at all to get his effect, whereas Gordon who also got great chiaroscuro effects, used tons of light. But the shots were always beautiful. Sven didn’t use any light, and his approach to getting these beautiful molded depths and shadows and chiaroscuro effects I guess stemmed from working with Bergman, when they had no money and no time to shoot. It would take Sven no time to light, and he was using nothing and somehow he knew, because I didn’t know, that if he used one little light in a certain place, you could get the same effect as someone who lit with many, many lights. And, you know, I’ve since worked with Darius Khondji, Vilmos Zsigmond, and Vittorio Storaro, these people all worked with a lot of lights, such as in Midnight in Paris which was beautifully shot by Darius Khondji, and he used a million lights, and it was the same deal with Vittorio. But not Sven! Sven for some reason just mastered the art of getting beautiful effects with minimal lighting. Sven, also, with Bergman, was essentially a black-and-white photographer, and that is very beautiful, but it becomes so much more complicated in color. It’s possible that if Sven had always worked in color he would’ve had to work much harder. But when I worked with him, he was quicker than any other photographer that I ever worked with.

TI: Do you think you’ve always had the good fortune of working with trained professional actors with whom filmmaking and acting always come naturally and easily? I remember reading an interview with you where you said that the sisters in Hannah and Her Sisters would always intrinsically know what to do. Did you have that same experience in your filmmaking where you could see what you wanted and it came naturally to you?

WA: Yes. It came naturally because when I started I was making just comedies, and I could always imagine what would be funny on the screen, and I was right enough of the time so that the film worked. I wasn’t always right, there would be times when I thought something was hilarious and it wasn’t funny at all. But for the most part, I could guess correctly, and then I found over the years that the people I worked with, who were top-notch actors and great photographers, I hardly had to direct them. The photographers worked with me closely and we always had very good relationships, and I never had to tell them much. I would just film them and watch them, and direct them if they made a mistake, but they understood what was required when they read the script, and then they executed it because they knew what they were doing. Once in a while, I would have to say something like “Could you be a little angrier here,” or “Play that scene a little quicker,” but I did very little, and it worked out fine. This has always been my approach, and it’s also why I would never be a good film teacher; I’m all instinctive. I couldn’t tell you how I was writing something, or how I was filming it, it’s what it felt like at the time. Something ever felt right, or it didn’t. If it felt right, I could rely on it most of the time. It wasn’t unfailing all of the time, but it was reliable enough so that most of the time I could make a film and it could come out coherent and reasonable. And I found that to be true with many people I worked with—we would go location hunting and look at a house, thinking whether we would use it for the protagonist or not. We would debate, but somehow always the cameraman or I would say “This one feels better than the other one,” or “This take feels better than the other one,” or “This actor feels better for the role.” We would always go with that feeling, and it’s not something that you can exactly teach, it’s not a science. We would go by feeling, all the time.

TI: One final question: You shot your last film in Paris, and it was your first in the French language. At this stage in your career, do you feel more at home in New York or Paris?

WA: I feel more at home in New York, definitely., I adore Paris and I could live there, but I don’t think I’d like to keep making films in another language. I could do it, but it’s not ideal. I wanted to do it in English at first, but then I figured that my whole life I wanted to be a foreign filmmaker because everyone I idolized was foreign, so I thought maybe I’d make it in French, but I didn’t think anyone would let me because as soon as the picture in another language the box office dips. So I asked whether I could make it in French and they said sure, so I was taken with it and I made it. It wasn’t hard to do, but I would much prefer to work in my own country. If I ever do another film, I would do it here if I could, but sometimes the financing comes from a different country. I’ll get a phone call from Italy or Spain and they say they’ll put up the millions of dollars if I shoot in Rome or Barcelona, and I do it because it’s hard to resist that. But I’m definitely most comfortable in the United States, and more specifically in New York.